Here, Take It, and Don’t Cry [Nadir Un Vayn Nisht]

The evening of Sunday 8th February 1942 saw an elite group of actors, writers and singers come together to celebrate the work of their friend and colleague, Jakub Obarzanek, then at the height of his fame as an editor, comic writer and satirist. Within months all of them would be dead, shot or gassed in the concentration camps of Poland, executed because of their Jewish heritage or political comment, or both.

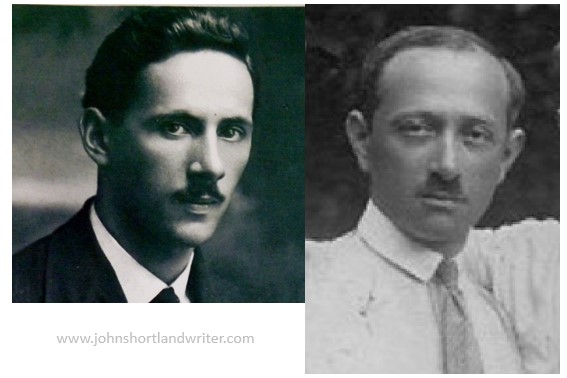

Jakub was born on 15th January 1891, probably in the city of Lodz where he lived for much of his life. The first son born to Samuel & Gitla, and into a comfortably off family, he would have been expected to follow in his father’s footsteps and work in the family business as a wholesale cloth merchant. However, Jakub had always wanted to write and in 1918 he published his first pieces of work – humorous songs and verses in the Lodzier Togblat, one of the premier Polish Jewish newspapers.

Writing always in Yiddish, Jakub very quickly developed a following amongst his readers and soon joined the permanent staff, editing and writing for the Friday edition. As his talent develops, he begins writing sketches satirising everyday Jewish Street life which, again is eagerly read by a public wanting more. During this time, he also begins collaborating with various revue theatres writing witty sketches, songs and monologues. All was going well until 1939 when the Germans invaded Poland, arriving in Lodz on September 8th.

One of the first moves the Gestapo made was to arrest Jewish writers and intelligentsia and Jakub along with others was taken to Radogoszcz, a factory now being used as a prison. It had no baths or kitchens. Almost immediately the killings began with the intelligentsia taken into nearby woods and shot. For reasons unknown, Jakub was freed in early 1940, possibly because a ransom of 150 marks would permit prisoners to be relocated to the Lodz Ghetto. However, sometime during 1940 he had made his way – or perhaps been taken – to Warsaw. Here, confined in the Ghetto he continues with his writing, helps to create a new revue theatre and providing them with material. The last we hear of Jakub is the evening performance celebrating his work.

It is not known whether Jakub was present for the performance. My feeling is probably not. What we do know is that he was once again arrested and was finally executed during April 1943. Married to Mala, Jakub had a daughter, name sadly unknown, and two sons, Moshe and Simon. Mala and the girl perished in the death camps. Whether they died alongside Jakub is also unknown, or even if they were with him after he moved to Warsaw. Both Moshe and Simon survived the concentration camps but were very badly traumatised by their childhood suffering. They ended their days in Israel but I have little knowledge of whether they were able to lead a full and fulfilling life.

The performers at the celebration of Jakub’s work were, as mentioned celebrated artists of their day.

Zymra Zeligfeld – a famous singer of Yiddish folk songs – murdered in Treblinka Death Camp, 1942

Chana Lerner – actress and wife of Dawid Zajderman, tenor – murdered together 3rd November 1943, Majdanek Death Camp

Symche Fostel – comic actor of International renown – murdered in Pontiatowa Death Camp, 1943

Jack Lewi – actor of International renown & close friend of Franz Kafka – murdered in Treblinka Death Camp, 1942 A(jzyk) Samberg – famous Jewish actor – murdered in Poniatowa Death Camp 1943 Prof (Icchak) Zaks – founded the Internationally renowned, 120-strong Icchak Zaks Chorus; researcher and translator of opera into Yiddish, and music teacher – murdered in Treblinka Death Camp, 1942

all had been executed by the end of 1943 [Wikipedia]

Jakub, as has been shown, was a popular man, much admired by his friends and colleagues; he must have been a brave man too and not only with his satirical writing and working knowing that he was unlikely to survive the war. Earlier, just prior to WW1, my grandfather, Harry Obarzanek, Jakub’s younger brother had been living in England when he was conscripted into the Russian army (Poland at that time was part-under Russian control). Now in army camp in Ukraine, he wrote to Jakub telling of his anxiety of being away from his wife for three years. Jakub arrived bringing false papers, civilian clothes and a ticket to England and helped Harry abscond whilst on duty. If they had been caught both would have been shot. If it hadn’t been for my great-uncle Jakub’s help, perhaps my own family would have suffered the same terrible fate as Jakub’s. A humbling thought. I hope that with my writing, I have given Jakub the voice that was so very nearly lost, and that it is an adequate tribute to our brave and witty family hero.

How appropriate it seems that I am able to write about Jakub’s life and publish it on the 80th anniversary of his death. A very special thanks to Chaya Bercovici who saw my initial Facebook plea for information relating to Jakub and, by some miracle, remembered hearing of my grandfather’s escape from Poland. Is it too fanciful that Jakub, knowing of this, might have said, “Nadir un vayn nisht”, “Here, take it, and don’t cry”, the words used as the title to his tribute evening?

.

Comments

Post a Comment